Words and Images by J.R. Ayala

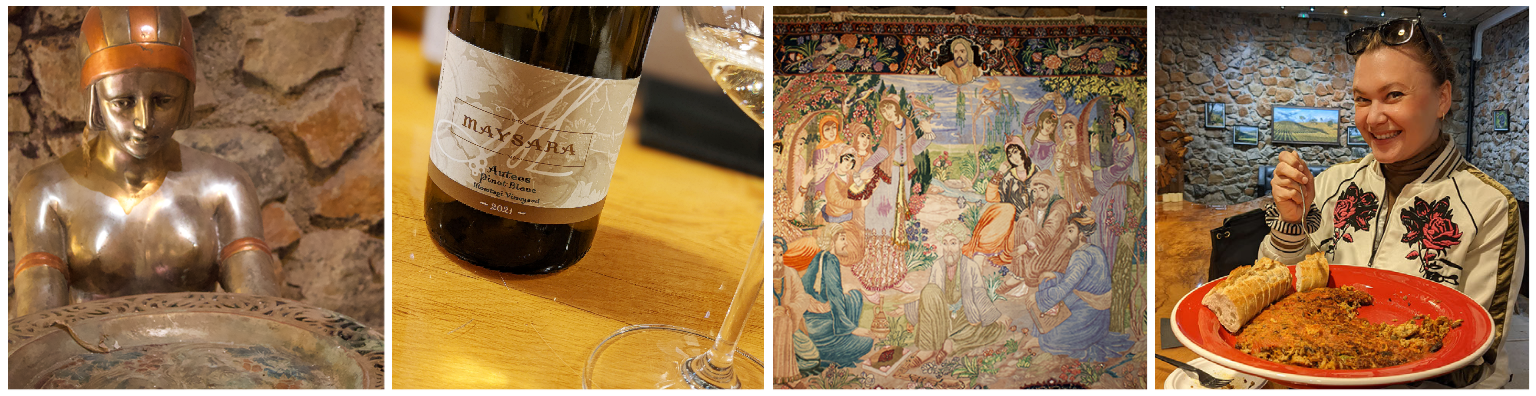

Lola, Derek (Assistant Director of Sales, North Texas), Moe and Craig (Assistant Regional Director, Houston)

At Maysara, its magnitude reveals itself slowly. Upon first arriving the estate is completely eclipsed from the highway by a row of forest. The entryway trails between these trees and small, hilly vineyards that slope up, creating a skyline without hinting at the landscape beyond its crest. There’s a brook that parallels the drive to the winery tasting room, the murmuring kind, and tiny Oregonian wildflowers that I do not recognize. Whenever I visit a winery I search for it— the pungent, familiar punch of yeast that usually betrays fermentation. It’s there and it’s faint, cloyed by morning mist, mild piles of compost, Spring grasses, and a picaresque openness.

We were greeted by the deliberately charming patriarch and co-owner, Moe Momtazi himself. It was nine a.m. on a dewy Saturday morning in McMinnville and we opted to sit just outside of the arched doors of the winery. Although I had been warned prior to this visit as to how quickly the weather could change from mild to unbearably cold, and had been advised as to just how endearing the Maysara experience would be, I was unprepared for both. We immediately launched into a tasting while Moe and Dominic, their hospitality manager, guided us through several wines. We were in Pinot country for breakfast— it’s own kind of magic and its own kind of strange.

To make matters slightly stranger, somewhere off in the distance was mooing. An incredibly forceful, loud amount of mooing. Between polite, focused sips we asked what all of the hullabaloo was about. We already knew that as a biodynamic farm cows were an important part of their 500-plus acre ecosystem— for grazing, manure, and various preparations. Moe explained: they hadn’t had a bull on their land for some time. The herd size was just right. And then one fateful day an immature bull on a neighboring property overcame a broken fence.

“We didn’t think about the young bull… activating,” he said, a little embarrassed. A little bemused. Their herd size had abruptly grown and both the cows and the calves clearly had something to say about it.

While I know next to nothing about animal propagation, I don’t think any of us expected such an honest answer. It was impossible not to laugh and any seriousness underscoring our visit instantly vanished. We’d incidentally received an insider look at how animal husbandry can play out in biodynamics: when a farmer provides the conditions for their animals to naturally thrive, they just might do so. After our lesson in “activation” the air characteristically chilled and we redirected inside. Moe ushered us along to continue to taste (sans heifers) and lent us to Dominic for a spell.

In the tasting room the globe of my glass is large and when I casually spin my wine it sloshes in a deeply unsatisfying wave to one side. I correct, introducing air and momentum, enjoying the forgiveness of the bulb. The cherry-bright swirl we’re sampling is the 2014 Jamsheed Pinot Noir, a Serendipity favorite.

Dominic explains the wine to us in detail. It’s a blend of Pommard and Wadenswil clones using a native ferment. Mostly neutral French oak. I learn later that the Persian legend this wine was named after, King Jamsheed, was “able to observe his entire realm by peering into his full wine goblet.” When I taste the wine the fruit is both bright and brooding. The earth is as light as steeped tea and as dense as beetroot. Dominic reveals that Maysara doesn’t release their wines chronologically and before I can process my surprise I realize the wine is 8 years old and it’s pristine. They encourage tasting a wine over the length of several days and noting transformations. It’s one of the many reasons they use ecologically sound screw caps instead of cork.

We taste through several other Pinots, including the ‘Mahtaub’, a whole cluster offering that helps to support Maysara’s many land stewards. And a Pinot Blanc (Autees!) with so much depth and generosity of character that I could have left on that note and been satisfied for the rest of the day. When Moe reemerges he’s holding a platter large enough to feed our small group twice. He’s whipped up a saffron-red, Russian dish shaped like an enormous latkes. It’s clear that his holistic approach to nurturing the land effortlessly translated to hospitality. We eat and we sip and the tasting room fills with faces of Maysara regulars and other curious newcomers. When we’ve had our fill, we trek out back for a tour of the vineyard with Moe.

For this drive we pile into his SUV, leaving behind the newly-bustling tasting room. We begin our ascent over the first of many sloping, verdant hills and he explains that the vineyards are entirely contiguous. Every plot is connected to every other plot. As we reach new elevations it becomes clear that at no one point could you actually take in the entire property— it is too far reaching. Each twist brings new sites and historic markers. Buildings he’d designed and built where production used to take place. That one spot his cows refused to graze, overgrown with weeds. He points out several bodies of water. As an engineer Moe had constructed a way to irrigate using their own unique water table. Even the brook that veined its way through the winery entrance played a role in sustaining the land.

The vines are in that stumpy phase of their life cycle when the thickness of their trunks are in harsh opposition to their own skinny, outstretched arms. Mustard flowers occasionally fill the rows and complete their duties as pretty cover crops: increasing organic compounds in the soil, creating biofumigants to ward off pests, and redistributing nitrogen. Branch trimmings intentionally left between the vines will later become tea and added to compost heaps. I’d never thought about the life cycle of treated compost before, but Moe mentions that piles, some larger than 12ft long, would take years to decompose to be used throughout their land.

At this point in our trip we were giddy with questions, excited to identify a mosquito if we thought it might have contributed to their biodynamic process. We point at everything we see like overly eager children, in an endlessly demanding chorus of “What’s that? And that? And THAT?” To which Moe eventually responded, “These plants right in here— that’s poison hemlock. A little bit of that, if you put it in your mouth, instantly kills you.” We learn that poison hemlock loves organic soil and that these wild growths are both useless and undesirable in the Maysara kingdom. Foragers, beware.

As we pleasantly pilot over dirt paths Moe speaks about his family in Iran. I’d read about his story long before I tasted their wines, of fleeing Iran and revolution with his wife, Flora. I had been struck by something he once told a journalist about low-intervention winemaking: “My grandfather was a farmer in the old country, and back then we didn’t call it biodynamics or anything like that, we just called it ‘natural farming.’” He ruefully explains how he’d hoped to be able to plant native Iranian varieties in Oregon. Despite some enthusiastic efforts from his brother to make that happen, it wasn’t (currently) meant to be.

After a few short hours of tasting, questions, cows and connections, our gentle meandering came to a close. Moe is the sort of person who speaks with such focus and warmth that it would have been easy to listen to him for many more hours, and I am of the firm opinion that everybody should. Until the next time I’ll be back in Longhorn country, pouring one of their Pinots over the course of several days, observing how Maysara continues to reveal itself over time.

Explore Maysara

Click to explore more of Maysara’s current offerings with Serendipity: